The First Pikes Peak Hill Climb

- Mike Bryant

- Jun 20, 2025

- 10 min read

By Mike Bryant

June 20, 2025

Racing superstar Ralph Mulford had won the day with a time of just 18 minutes, 24 seconds—more than 5 minutes faster than his next closest competitor. The previous day’s winner had taken over 23 minutes to complete the same course. A correspondent for The Rocky Mountain News marveled, “Mulford’s time means he drove all the way up to the top of this mighty mountain on this road of twists and curves at an average speed of better than forty miles an hour.” It was August 11, 1916—Day 2 of the three-day extravaganza known as the Pikes Peak Hill Climb—and already Mulford had exceeded expectations in thrilling fashion.

But the real contest was yet to come.

The first two days had been more or less an exhibition. It would be the race on Day 3—the “free for all” it was being called—that would decide who walked away with the $2000 cash prize and staked a claim to the glittering Penrose Trophy. Surely Mulford was the favorite to win, but in auto racing there was always that “element of chance” as the News was quick to point out. In his race he had actually been behind the famous English driver Hughie Hughes “by at least the larger part of a minute.” But then “there was a rumbling and a jarring and in a minute the chances of Hughes and his Duesenberg were gone. A piston had become loosened and drove through the bottom of the crank case.” Chance had worked in Mulford’s favor, but tomorrow he would have to reckon with Rea Lentz and his custom Romana. Rumor held that the Romana was powered by an eight-cylinder 175 horsepower airplane engine. And, the News correspondent added, “Hal Brinker… and his Cadillac also are entered and he may have something up his sleeve.” But Mulford’s time of under 19 minutes—that was unheard of, and, besides, the hill climb with its dozens of hairpin turns would be more a test of man than machine, and Mulford was probably the most famous race car driver in America…

The Pikes Peak Hill Climb was the brainchild of Colorado Springs millionaire Spencer Penrose, an ingenious way of promoting the new Pikes Peak Auto Highway that had been completed only a few weeks earlier. Modern writers usually give primary credit for the highway to Penrose, but it had been Eugene A. Sunderlin who conceived the project and who served as president of the company that built the road. Penrose was an early financial backer of the venture and no doubt brought the political clout needed to make it possible, because the highway ran through the Pike National Forest. As The Lyons Recorder reported on October 28, 1915,

Before Congress closed its sixty-third session, it granted the right-of-way for an automobile road that would traverse the Pike national forest and wind its way up the northern slopes to the top of the peak. When the government granted this right-of-way through a national forest for a toll road, it did an unprecedented thing.

Sunderlin had a good idea, but he was a nobody in the eyes of the Washington power brokers. Penrose, on the other hand, was not only a millionaire and famous philanthropist, but also the brother of one of Washington’s own: Pennsylvania Senator Boies Penrose.

Spencer Penrose was civic minded and surely saw the tourism dollars a road to the top of “America’s Mountain” would bring to his adopted hometown of Colorado Springs. He was also a shrewd businessman and may have already been contemplating his grand resort The Broadmoor when he invested in Sunderlin’s idea of replacing the dusty carriage road up Pikes Peak with a modern automobile highway. After paying tolls to Penrose and his partners to ascend Pikes Peak ($2 per person or $5 per car), those tourists would need a place to sleep, eat and relax.

In 1915, the year construction began on the Pikes Peak Highway, the automobile was reaching a point of critical mass in American culture. It had been seven years since Henry Ford had introduced his Model T and made motorcars affordable for the masses. The Rocky Mountain News profiled this epochal shift in its edition of August 13, 1916:

The wonderful advance of the industry was depicted in the people who rode in the automobiles. A few years ago the man with the chauffeur and the high priced car would have been in evidence during race week. At the Springs he was in the minority. Not that the rich man, the man of leisure, was not out in force, but he was set into the background by the men and women of smaller means.

The News quoted an engineer from the Chalmers auto manufacturing company as saying,

The people, the common people of this country, are just beginning to find out what the automobile can do. They take a trip of 3,000 miles now, where a few years ago a ride to a city park was considered a long jaunt. In a few more years 500,000 automobiles will come into Colorado each year.

The News thought they had detected the secret reason for the automobile’s ascendancy: a companion article found in that same edition was headlined “Auto makes women happy, spend less on finery.”

Penrose and Sunderlin timed their project brilliantly.

Construction of the road proved slower, more costly, and more difficult than Penrose had envisioned. First, there were the government inspections. “It runs through the Pike’s Peak National forest [sic],” Penrose told Leadville’s Herald Democrat (July 17, 1916), “and we were delayed somewhat, waiting for the government engineers to approve the construction. It was built as a public enterprise and was not backed by the government, but owing to its location, the survey and the construction work had to be accomplished under government supervision.” Finding labor was also a problem, due to the dizzying altitudes and harsh conditions of the jobsite. “On one day twenty-four agreed to go to work. They went up the hill to the place of construction and then came down again without having touched a shovel,” he told The Herald Democrat. All of this led to such delays that “we were not sure until recently of the time of its completion.”

In fact, there had been an extremely premature grand opening of sorts in September of 1915—ten months before its final completion. The road was still five miles from reaching the summit of Pikes Peak, but Sunderlin and Penrose invited scores of dignitaries, including the governor of Colorado and one of the state’s senators, to commemorate the progress. The Rocky Mountain News reported in its edition of September 2, 1915:

The guests were taken in the company’s special cars from the Antlers hotel, thru the Garden of the Gods, up Ute pass to Cascade and from there up the new automobile road, twelve miles to Glen Cove. Here a barbecue lunch was served, picnic style.

The governor and senator then both gave laudatory speeches. At that time, it was estimated the road would be completed the following April, which proved to be three months too optimistic.

These delays and other “countless difficulties” caused the project’s costs to explode. Penrose told The Herald Democrat, “The engineers estimated at first that the highway could be completed for about $80,000. Before it was finished it cost $200,000.” He gave this interview on July 17, 1916—one day after the final completion of the Pikes Peak Highway. He must have been quite relieved to see it completed, because he had been advertising for months that a race would be held on the new road in August. In other words, the project had been finished with just a few weeks to spare.

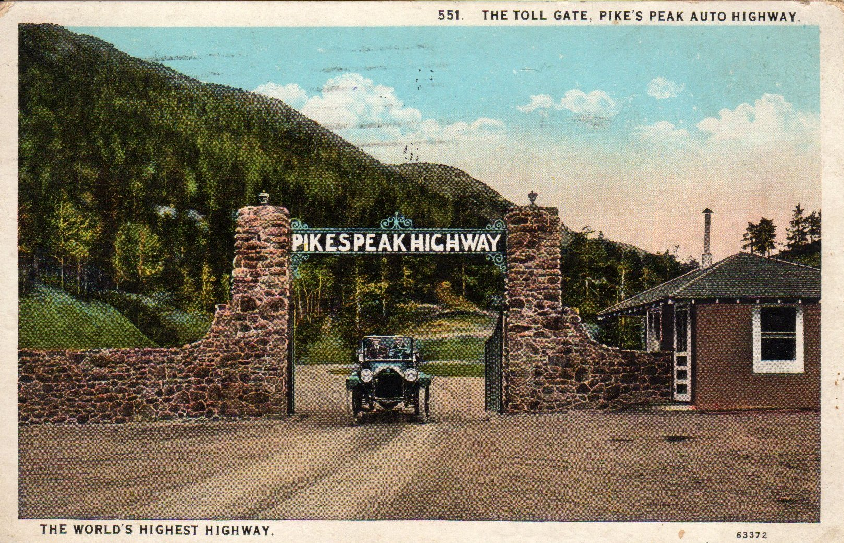

Behind schedule and over budget though it was, the road became an instant sensation. Journalist Harold Hill accompanied a “happy party” as they navigated the twisting road in a “big Packard Twin 35.” After a dusty trip down from Denver they finally reached the “gateway of Colorado’s most striking asset, Pikes Peak,” and the tollhouse of the new road, both of which were “beautifully built from cobblestones.” Hill found that Penrose and Sunderlin had taken great care to anticipate the needs of drivers in that age where automobiles were still temperamental machines prone to breaking down: “each three miles has its water tank and its phone. The water tanks are equipped with clever little devices so one may water the car by means of a hose and patent hydrant…The telephone,” he added, “is not only local, but long distance.”

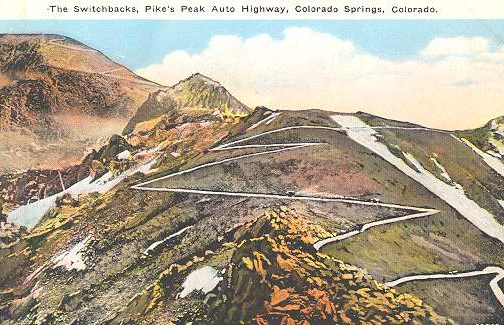

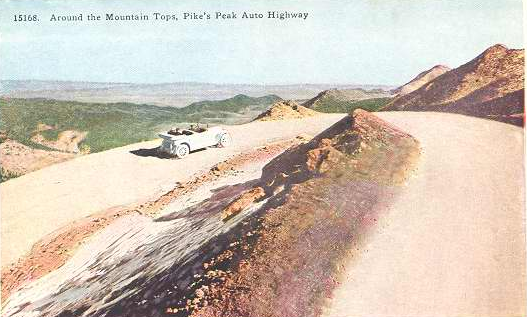

Other writers admired the width and gentle inclines of the winding road. “The road bed is 20 feet wide and this is increased to 26 feet on curves, making it possible to be double tracked all the way with frequent ‘turnout’ or stopping places provided in case of tire or engine trouble." There were gas stations at both the entrance and the summit, and “expert repair men always at hand.” It is important to understand that roads in 1916 were generally of very poor quality. Indeed, three years later a young lieutenant colonel named Dwight Eisenhower would participate in the army’s transcontinental motor convoy, undertaken “to test the mobility of the military during wartime conditions.” Eisenhower found that the nation’s roads were often “impassable and resulted in frequent breakdowns of the military vehicles.” The Pikes Peak Highway was, by contrast, a model of what a good road could be. Ralph W. Smith, vice president of the American Automobile Association told the Aspen Times Democrat (July 10, 1916),

I have traveled all over Continental Europe and America and nowhere have I seen such a remarkable road as the Pikes Peak Highway. It is without question the most marvelous example of highway engineering of the Twentieth Century and, owing to its extreme width and easy grades, is safer than most of our State roads.

But it was writer Helen Marsh Wixson who most poetically encapsulated the impact this engineering feat had on the American imagination. The sight of Pikes Peak’s snowy reaches, she wrote, had long

proclaimed to weary path-breakers that there was an end at last to the dreary waste of plains. And now even that great peak has been subjugated. It has bowed its white head in surrender and an automobile road, the world’s highest highway, leads to the summit.

In a very real way, the Pikes Peak Highway had become the emblem of the new automobile age.

Sunderlin and Penrose had built a masterpiece, but it had cost far more than anticipated. They and their partners needed a return on their investment, and that meant they needed to lure toll-paying visitors. They needed a spectacular event that would bring attention to their new road. Penrose contemplated a truck climb, after an enterprising truck manufacturer hauled a load of two tons up the partially completed road. But he knew that what would really fire the American imagination was a road race. There were already a number of hill climb races in places such as Pennsylvania, but nothing to compare with a race to the 14,000-foot summit of America’s most famous mountain. The Pikes Peak Hill Climb was born.

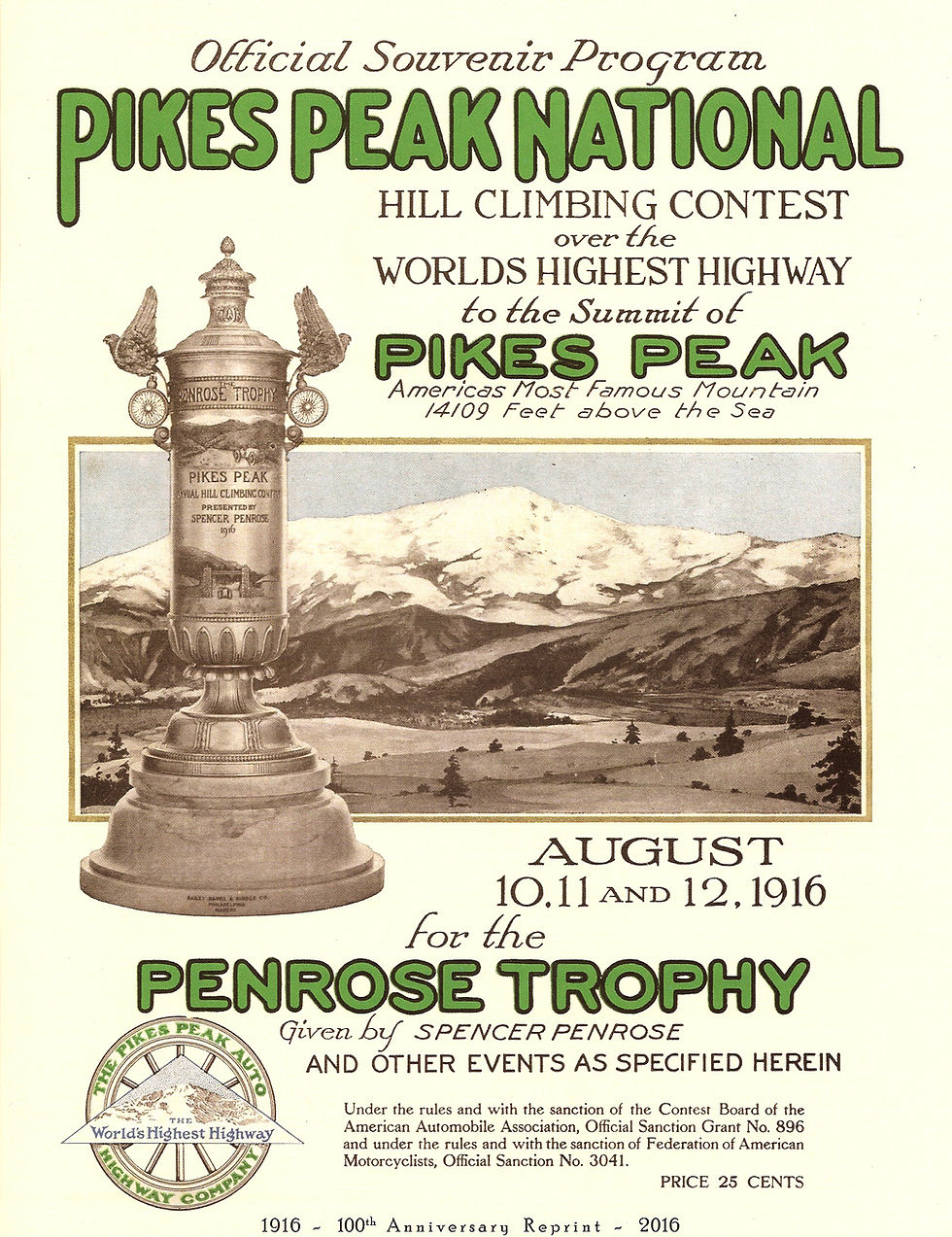

Penrose set out to make the race as attractive as possible, offering $7000 in prize money (including a purse of $2000 to the winner) and commissioning the Philadelphia jewelry firm Bailey, Banks and Biddle to fashion an elaborate three and a half foot tall trophy made of gold and silver extracted from mines in Colorado. The trophy cost $1200 (about $35,000 in 2025 dollars) and was itself put on tour to display in New York, Cleveland and Detroit before coming home to Colorado.

Originally, Penrose envisioned the race as an event open to all, and by July 9 there were over 200 entrants. Car makers like Hudson and Cadillac were rushing to ensure their cars were included in the high-profile contest. But a week later something happened that changed the situation entirely: “Ralph Mulford, noted race king, is the latest speed wizard who has entered the Pikes peak hill climb.” Mulford was perhaps the most famous race car driver in America. He held the world record for a 24-hour race and had taken the prestigious Vanderbilt Cup at a 1911 race in Savannah, Georgia. Some believed he had won the first Indianapolis 500 but that his victory had been stolen. His decision to participate in the Pikes Peak Hill Climb “ensured” the race’s success according to The Rocky Mountain News. Perhaps not coincidentally, the very next day Leadville’s Herald Democrat reported that the race would be restricted to just professional drivers (and a few amateurs with significant racing experience). The explanation given was that “the entrance of amateurs would make the race dangerous.” The Herald Democrat further reported that this decision had been made as a result of a meeting between the race’s manager and contest board officials of the American Automobile Association. Penrose may have been leaning in this direction anyway—a fatality could poison perceptions of his highway, and, more importantly, he was a man of conscience—but Mulford’s entrance at least assured that the event would get national attention if he did opt for safety and a more limited field.

The race—actually a series of races—took place over three days: August 10-12, 1916. Mulford astonished the crowd with his performance on Day 2, but, as we have seen, that was essentially an exhibition run. It was the “free for all” on Day 3 that would determine the winner. Conditions for that race on August 12 were abysmal:

Much of the race was run thru a driving storm of rain, hail and snow. Spectators who had journeyed far up the mountain to watch the drivers far below them shivered in the cold. Goggles worn by the racing crews were covered with frost and thrown aside.

If anything, the adverse conditions would seem to favor the more skilled driver, and Mulford had seemingly proven himself as such by crushing his competition on Day 2. The only racer that had challenged him was out of commission with a thrown piston.

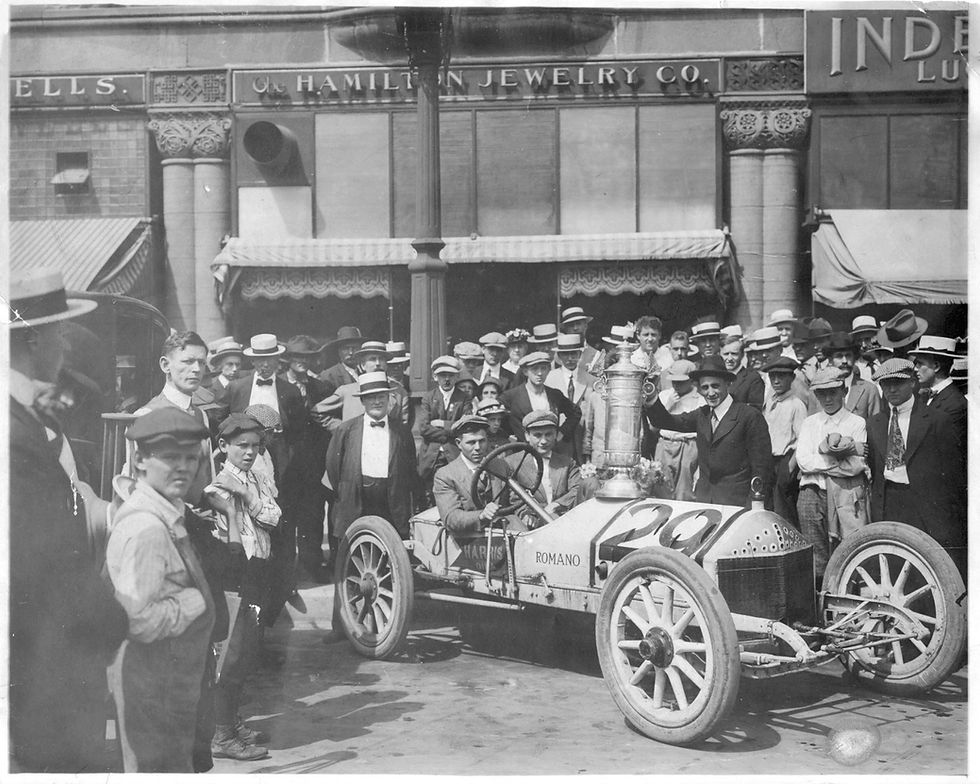

Rea Lentz, described as “a Seattle youth” (he was 22, a decade younger than the veteran Mulford), was a little-known driver who had traveled to Colorado from Seattle “on a shoestring. He had no money beyond the entry fee and a short, very short, expense account.” He was driving a machine custom built for him by an “old mechanician” named Jules Romano. It was the smallest car in the field, “a car that all the other drivers had termed a misfit.” That dismissive view changed, though, once “they saw it perform on the road.” The car’s body was small but the engine’s displacement was huge, the biggest in the race. It provided an interesting twist on the David vs. Goliath narrative—young Lentz was armed with a bazooka rather than a slingshot, and, it turned out, he knew how to use it. Lentz and his Romano won the first Pikes Peak Hill Climb in a time of 20 minutes, 55 seconds, beating Mulford by about 45 seconds. The old veteran still held the course record, set the day before, but in an odd twist of circumstances it was not his name that would be engraved on the Penrose Trophy.

There was always an asterisk next to Roger Maris’ record 61 single-season home runs; he had beaten Babe Ruth’s record, but in a season 8 games longer than when Ruth played. A case could be made for adding one next to Rea Lentz’s victory in the first Hill Climb. But then again, he beat his opponent in a head-to-head matchup, and weather surely had impacted performances. In that way, it was a fitting start to the Hill Climb’s storied history of racers facing off under some of the toughest conditions imaginable.

Download a PDF of this article with footnotes

.png)

Comments